First, of all, I just want to say that it’s a little strange to be on the other side of the glass here at the Flexner reading group blog.

For my first post I want to talk a little bit about why I, as a historian-in-training, find Butler’s work useful. Her analysis of the performativity of gender was formulated in response to a set of modern philosophical texts (Nietszche, Hegel, Freud, Foucault) and cultural trends (feminism, drag, and the gay rights movement), so it’s not immediately obvious that it should be useful to someone studying earlier moments in history. It turns out, though, that the discursive and embodied practices through which gender is constructed have changed remarkably little since the beginnings of written history. While the performances of gender may have changed (today Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man comes of as slightly sassy when compared to, oh, say, the normative Leading Man du jour Sam Worthington), the use, or pointed neglect, of haircuts, clothes, words, cosmetics, gestures, etc., to perform gender has not. The means by which legitimate subjectivities are determined have remained less static, although even these often extend to the hazy dawn of the nation-state if not much earlier.

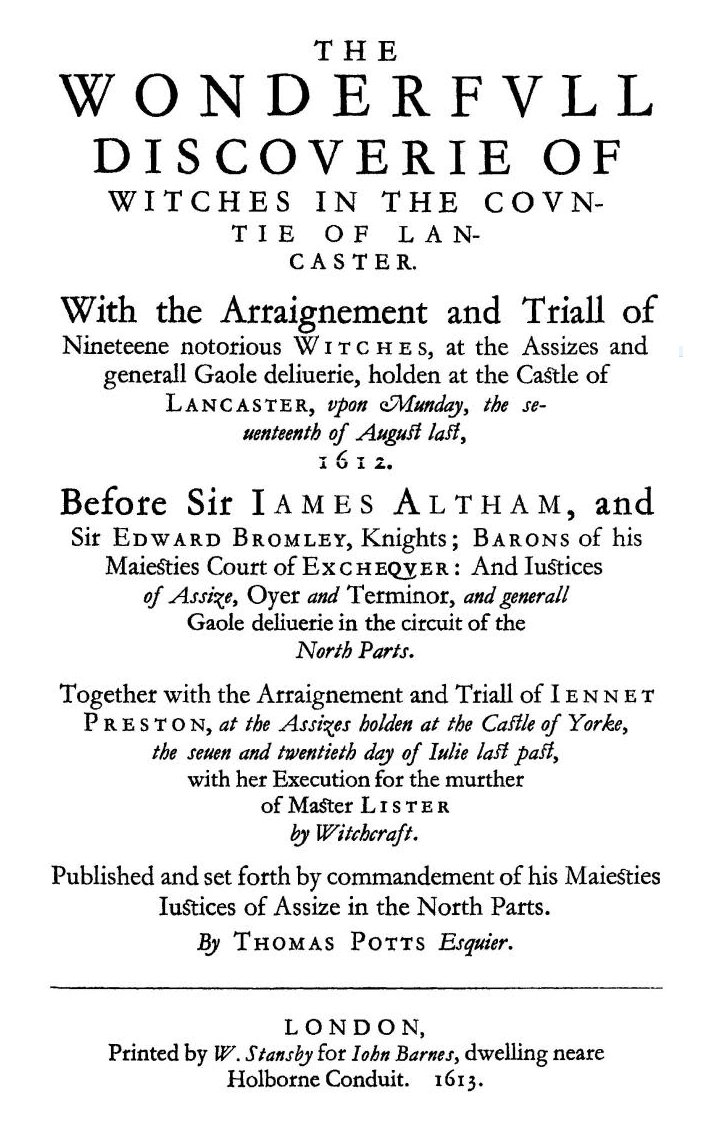

Take Early-Modern witches as an example. I’d say that Halloween got me thinking about them, but I’ve just been listening to a lot of Demdike Stare. In 1612, nine women and two men from the area around Pendle Hill, north of Manchester, were found guilty of witchcraft and executed by hanging. Thomas Potts, the clerk to the court, published the official proceedings as a book titled THE WONDERFVLL DISCOVERIE OF WITCHES IN THE COVNTIE OF LANCASTER.

As I was reading the first chapter of Excitable Speech, I was struck by the parallels between the hate speech trials that form the subject of Butler’s study and the Pendle witch trials. Both are characterized by anxieties about the tenuous connection between speech, intent, and injury, and both elide the way in which judicial speech itself enacts violence.

The Pendle trials, however, are framed not only in terms of the individual and the state, but also in terms of religion. The entire discursive framework of the trials was structured by the religious turmoil of 16th-century England and the air of paranoia that it created. And while witches may not have been new, they were certainly receiving large quantities of bad press: King James I personally attended the trial of the North Berwick witches, accused of attempting to sink his ship as he returned from his marriage to the Danish princess Anne, and he wrote a strange little book called Daemonologie. The privileged speech of the King, centered on an appeal to Christian scripture, certainly influenced the proceedings.

The separation of church and state that’s unproblematically assumed in Butler’s case-study doesn’t apply to this earlier moment, so we can’t simply read the Pendle trials through Butler. But her framework allows us to perceive the overlapping systems that are actively erasing their own agency in constructing the very subjects that they prosecute and kill.